Life is complicated. Regardless of what your beliefs or politics or ethics are, the way that we set up our society and economy will often force you to act against them: You might not want to fly somewhere but your employer will not accept another mode of transportation, you want to eat vegan but are at some point in a situation where the best you can do is a vegetarian option.

Sometimes it’s not even our hand being forced but us not having the mental strength or priorities to do something: I could just not use WhatsApp because it is owned by Meta but my son’s daycare organizes everything through WhatsApp and do I really want to force my belief on all those very busy parents and caretakers or should I just bite the bullet and use the tool that seems to work for everyone – even though it’s not perfect?

There are no one-size-fits-all solutions for this: Sometimes a belief or ethic you hold is so integral to you that you will not move. Sometimes they are held loosely enough to let go under certain conditions. There’s a multitude of factors and thoughts that go into those kinds of decisions and at some point you just gotta make a call based on what’s in front of you and your priorities.

What I am saying is: We are all doing things we know are not ideal, are either morally questionable or do not align with our values. That’s life. I for example know that consuming meat is problematic for ethical and ecological reasons, I still do it sometimes. I reduce as much as I can but I am far from perfect. Just one of the many examples of my actions not being perfectly and purely aligned with my beliefs.

And I am 100% sure each and every reader will have similar experiences. We are imperfect and messy beings. In the end all you can do is actually try to make good decisions based on your values, try to learn from your actions and ideally do better – or at least understand what were the forces that go you to act against your values.

Cory Doctorow, probably one of the most influential writers about digital technology and culture celebrated the 6th anniversary of his personal blog pluralistic – congratulations! Cory is quite the phenomenon, I know nobody with his amount of output and his consistency of publication. It is scary just how consistently he writes and published while also churning out books. I do admire his work ethic tremendously.

But one thing in his celebratory post rubbed me the wrong way and I think it’s worth pointing out. Not for the one specific case but because it highlights a problematic way of thinking that I see a lot in current tech discourse that stands in the way of us actually improving the world.

So Cory outlines his process of how he publishes to his blog (and then pushes the same writing out to other places). He describes how one QA step in his process is piping his writing through an LLM (using the Ollama software, it’s unclear which open weight LLM he uses) to check for typos and small grammar mistakes. He then points out how some readers might find that problematic:

“Doubtless some of you are affronted by my modest use of an LLM. You think that LLMs are “fruits of the poisoned tree” and must be eschewed because they are saturated with the sin of their origins. I think this is a very bad take, the kind of rathole that purity culture always ends up in.”

Using LLMs isn’t always popular with the cool crowd, Cory knows that. And he wants to defend his (quite modest) use, which I understand: Nobody likes their problematic behavior being pointed out to them. But as outlined: Life’s complicated. Cory could just have said “I know there are many critiques of LLMs, but right now that is the best way for me to enable my work, I try to limit the problematic aspects by using a small open weight model and checking the results in detail.” and have moved on. But he needed to make a stand. And that stand lead him into the problematic train of thought that I wanted to point out here. Because many, many people listen to him and basically take his word as the gospel. So great power, great responsibility and such.

The whole argument is based on a strawman. Let’s look at Cory’s words:

Let’s start with some context. If you don’t want to use technology that was created under immoral circumstances or that sprang from an immoral mind, then you are totally fucked. I mean, all the way down to the silicon chips in your device, which can never be fully disentangled from the odious, paranoid racist William Shockley, who won the Nobel Prize for co-inventing the silicon transistor

Cory is right in pointing out that almost any technology we have has been touch by problematic figures. Racists, fascists, sexists, rapists. You name it. Anything you touch will have some research or engineering or product work by a person you despise in it.

The strawman is his claim that people who criticize LLM usage are doing that for some form of absolutist reasons. That they have a fully binary view of the world as separated into “acceptable, pure things” and “garbage”. Which is of course false. Because they are using a computer, using warm water that’s probably heated through the use of fossil fuels etc.

He attacks a ridiculous made-up figure to deflect from specific criticism of LLM use (that many probably wouldn’t even apply that strongly to his use case). But that’s not where criticism of LLMs comes from: It’s mostly specific focussing on the material properties of these systems, their production and use.

Cory continues:

“Refusing to use a technology because the people who developed it were indefensible creeps is a self-owning dead-end. You know what’s better than refusing to use a technology because you hate its creators? Seizing that technology and making it your own. Don’t like the fact that a convicted monopolist has a death-grip on networking? Steal its protocol, release a free software version of it, and leave it in your dust:”

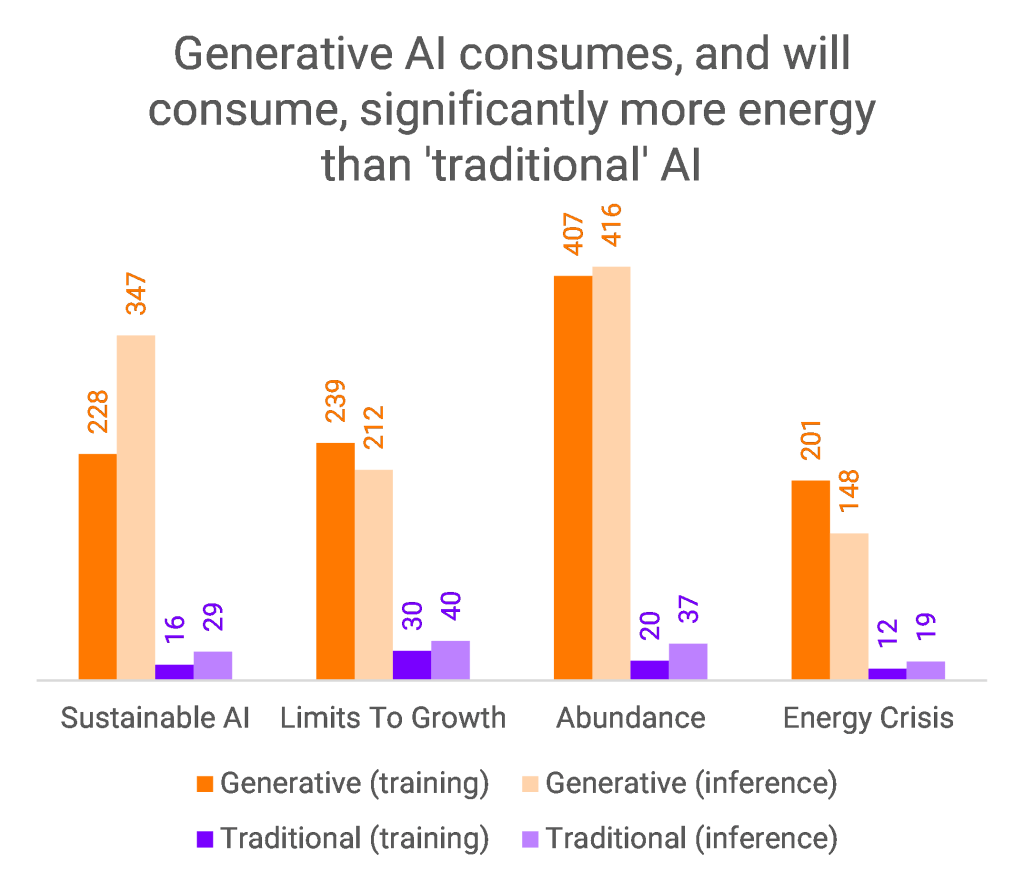

Here again Cory is misrepresenting the LLM-critic’s argument: Sam Altman is a scam artist and habitual liar, but that’s not one of the first 10 to 20 reasons people criticise OpenAI’s products. Sure, basically every leading figure in the “AI” space seems to be unpleasant at best but that’s true for most of tech TBH. People criticise LLMs for their structural properties, their material impacts, for the way they make it harder to learn and grow, for the way they make products worse while creating massive negative externalities in the form of emissions, water use and e-waste. For the way these systems can only be build by taking every piece of data – regardless of whether the authors consent or even explicitly refuse and how the training needs ungodly amounts of harmful, exploitative labor done mostly by people in countries from the global majority. How it materially harms the commons.

Even if OpenAI was run by decent, ethical, friendly, trustworthy people (which would then of course make them not work on the products OpenAI has, but it’s just a thought experiment) their products would need to be criticized for what they are and what they do. It’s really not about these few dudes running the companies.

Cory misrepresents the arguments (well basically hides them) in order to not have to face any material criticism and turns them into “you just don’t like these people” which frames the criticism as emotional and not rational. As if it was about not liking a bunch of rich men.

He then goes into how the path forward is to “steal the protocol”. His following paragraph goes into detail:

“That’s how we make good tech: not by insisting that all its inputs be free from sin, but by purging that wickedness by liberating the technology from its monstrous forebears and making free and open versions of it”

And here we are coming to the core of the problematic argument. Because Cory implicitly argues that technology is neutral and that one can just change its meaning and effect through usage. But as Langdon Winner argues in his famous essay “Do artifacts have politics” artifacts have built-in politics deriving from their structure. A famous example is the nuclear power plant: Due to the danger of these plants, their needs with regards to resources as well as security power plants imply a certain form of political arrangement based on having a strong security force/army and a way to force these facilities (and facilities to store the waste in) upon communities potentially against their will.

Artifacts and technologies have certain logics built into their structure that do require certain arrangements around them or that bring forward certain arrangements. The second aspect is often illustrated by how ships are organized: Because ships are sometimes in dangerous situations and sometimes critical decisions need to be made, the existence of ships implies the existence of a hierarchy of power relationships with a captain having the final say. Because democracy would be too slow at times. These politics are built into the artifact.

Understanding this you cannot take any technology and “make it good”. Is a torturing device “good” if the plans on how to build it are creative commons? Do we need to answer the existence of the digital torment nexus by building an open source torment nexus? I’d argue we need to destroy it – regardless of what license it is released under.

That does not mean that it is impossible to take certain technologies or artifacts and try to reframe them, change their meaning. In some way computers are one such example: They were first used by governments, banks and other corporations to reach their goals but where then taken and reframed to devices intended to support personal liberation. It’s a bit more complicated (for why dive into the late David Golumbia’s “The Cultural Logic of Computation”) but let’s give that one to Cory. Sure, sometimes it is possible to take something originally built for nefarious purposes and find better uses for it. But is that true for everything? Very obviously not.

Let’s just look at the embedded politics of LLMs: In order to train a capable system you need data. Lots of it. AI companies keep buying books to scan them, they download everything from every legal or illegal source claiming “fair use” (a doctrine that only applies to the US by the way) or that “scraping is always okay”. Capable LLMs require a logic of dominance and of disregarding consent of the people producing the artifacts that are the raw material for the system. LLMs are based on extraction, exploitation and subjugation. Their politics is violence. How does one “liberate” that? What’s the case for open source violence?

He uses a so-called “open source LLM” and that’s very much how he presents his values but open-source LLMs do not really exist. You can download some weights but cannot understand what went into them or really change or reproduce them. Open source AI is just marketing and openwashing.

Cory shows his libertarian leanings here: If everything is somehow “free and open” then we have won. But “free and open” in this context usually means that “certain privileged groups have easy access to it and are not limited in what to do with it”. That’s one of the core problems with the whole “open Source” movement: That it reduces all struggle to if one can get their hands on the tools and has any restrictions to using them.

This also shines through in Cory arguing that we need to “liberate” technology. What a strange idea: Technology doesn’t need liberation, people do. Technologies are tools not what we actually care about. Sure, sometimes technologies can play a role in liberating people but just as often “freeing” a technology does quite the opposite to people: Ask the women who have massive amounts of nonconsensually created sexualized images and videos created of them whether they think that the “liberation” of stochastic images generators is liberating them? Technology doesn’t need to be free. It cannot be free because freedom as a concept applies to people.

And freedom is not the only value that we care about. Making everything “free” sounds cool but who pays for that freedom. Who pays for us having for example access to the freedom an open weight LLM brings? Our freedom as users rests on the exploitation of and violence against the people suffering the data centers, labeling the data for the training, the folks gathering the resources for NVIDIA to build chips. Freedom is not a zero-sum game but a lot of the freedoms that wealthy people in the right (which I am one of) enjoy stem from other people’s lack thereof.

“Purity culture is such an obvious trap, an artifact of the neoliberal ideology that insists that the solution to all our problems is to shop very carefully, thus reducing all politics to personal consumption choices:”

Cory labels people’s values and their prioritization as “purity politics” (referring back to the black and white strawman the started this part of his post with) and then pulls a really interesting spin here: Many people criticizing LLMs come from a somewhat leftist (in contrast to Cory’s libertarian) background. Cory intentionally frames those leftist thoughts that put politics based on values as “neoliberal ideology” that reduces “all politics to personal consumption choices”. This is narrativecly clever: Tell those stupid leftists that they are just neoliberals, the thing they hate! Awesome.

But the argument against using LLMs is not about shopping and markets at all. My not using LLMs does not influence anything in that regard, Microsoft will just keep making the data center go BRRRRRRR.

In a way this framing shows more about Cory’s thinking that about that of the people he criticises: Cory is focused on markets and market dynamics and in that world it’s about purchasing. But moral choices only sometimes relate to markets. They do when I for example choose only to buy fairly produced garments. But when I for example refused conscription (when I was young Germany still forced every young man to learn how to kill) that was not a shopping decision. That was politics as well as leading an ethical life.

People do not believe that “not using LLMs” will solve the issue of OpenAI etc all existing. They do no want to build on, use products with so clearly defined harms and negative externalities. Because they believe it to be wrong. Sure, there might be a utilitarian argument for “the thing exists anyways and if it saves you time, that’s good, right” but many people are not utilitarians. They want to lead a life where they feel their actions align with their values. In a way that is a path to freedom: To having the freedom to make the decisions one feels are right are in alignment with one’s values.

Which Cory actually also believe and acts upon when it’s about his values: He has refused to create a Bluesky account in spite of wanting to be there cause his friends are there for (good!) ideological reasons: Because Bluesky was back then and honestly is still today mostly centralized with the Bluesky corporation having a central chokepoint to control the network. Cory believes that one sometimes needs to make decisions based on one’s values. He just does not think that your values as someone not wanting to use LLMs matter.

I mean, it was extraordinarily stupid for the Nazis to refuse Einstein’s work because it was “Jewish science,” but not merely because antisemitism is stupid.

Everybody hates Nazis. Implying that one is in any way like the Nazis is just a killer argument. But let’s talk about Nazis for a second. The Nazis did a lot of psychological and medical research. On people they interned and later killed in concentration camps. There actually was a massive debate within especially psychology whether using the results of that kind of research is ethically possible. Utilitarianism of course argues that if it’s there one should use it but especially when your whole discipline is focused on understanding how our psyche works in order to for example help people in trauma just taking research that has been created through unthinkable violence and torture feels wrong. Feels contrarian to what your whole discipline is there for. This reminds me of Ursula K. Le Guin’s story “The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas“: Omelas is an almost perfect city. Rich, democratic, pleasant. But it only works by having one small child in perpetual torment. Okay, but if that kid is already suffering because those other people chose to, should you walk away? Of just reap the fruits of that suffering?

Sometimes you need to walk away.

Cory then repeats the strawmen we already talked about and lands here:

“It’s not “unethical” to scrape the web in order to create and analyze data-sets. That’s just “a search engine””

Again, it twists the argument in the way that the AI corporations like to do it as well: Search engines scour the web so AI companies should be allowed the same. It’s the same technology! But what’s the purpose?

A search engine scrapes pages to build an “index” in order to let people find those pages. The scraping has value for the page and its owner as well because it leads to more people finding it and therefore connecting to the writer, journalist, musician, artist, etc. Search engines create connection.

AI scrapers do not guide people towards the original maker’s work. They extract it and reproduce it (often wrongly). “AI”‘s don’t point out to the web for you to find other’s work to relate to, they keep you in their loop and give you the answer cutting off any connection to the original sources.

While the technology of scraping is the same, the purpose and material effects of those two systems is massively different. Again, Cory misrepresents the critique and tries to make it look unreasonable by making it just a conversation about tech without regarding how that technology affects the world and the people in it.

I appreciate a lot of work Cory Doctorow has done in the last decades. But the arguments he presents here to defend his usage of LLMs for this rather trivial task (which TBH could probably be done reasonably well with traditional means) are part of why the Internet – and therefore the world – looks like it does right now. It’s a set of arguments that wants to delegitimize political and moral actions based on libertarian and utilitarian thinking.

Technologies are embedded not only in their deployment but also in their creation, conceptualization. They carry the understanding of the world that their makers believe in and reproduce those. A bit like an LLM reproduces the texts it learned from: It might not always be a 100% identical replica but it’s structurally so similar that the differences are surface level.

In order to build an Internet and a world that is more inclusive, fairer, freer we need to move past the dogma of unchecked innovation and technology. We need to re-politicize our conversations about technology and their effects and goals in order to build the structures (technological, political, social) we want. The structures that lead to a conviviality in harmony with the planet we all live on and will live on till the end of our days.

That path is paved with discussions about political and moral values. Discussions about how certain technological artifacts to align with those values or not.

I do agree with Cory that demanding perfect purity lead nowhere. We are imperfect people in an imperfect world. I just do not think that this means to go all accellerationalist. Just turning the “open source” dial up to 11 does not stop the apocalypse. It’s a lot harder.