Making big public statements is always fun and people who think themselves to be important love doing it as a way of trying to influence public opinion and/or politics. They are a way for institutions and individuals to organize and try to shine some light onto important issues.

We’ve seen many such things in the AI space, one of the more ludicrous examples being the big push to pause “AI” development (signed by a bunch of billionaires developing “AI”). With “AI” having sucked up all the air in the room what else could we declare things about?

Usually those declarations have a very short shelf-life, don’t really do much and are mostly harmless.

So there is a new declaration in town called the “The Pro-Human AI Declaration“. And before we go into the details, let’s look at who is pushing this for a second because the declaration keeps talking about how broad their coalition is.

And boy is that tent big. It’s big enough to proudly list Steve Bannon, one of the architects of the new wave of fascism as its second individual supporter. So it’s a declaration white nationalists and fascists can get on board with. Glenn Beck, another right wing talking head was also happy to put his name there.

But it’s not just right-wing grifters and fascists: Yoshua Bengio, Stuart Russell and many other academics from the field of computer science, they also got that part covered. Richard Branson of the Virgin Group is probably one of the bigger corporate names, there’s SAG-AFTRA leadership and a whole lot of religious organizations all sharing the stage with … well fascists.

There also is a lot of organizational support: Again SAG-AFTRA is joined by a whole bunch of ethical “AI” groups, religious groups and of course the Center for Humane Technology, known to jump on every bandwaggon that gets Tristan Harris some airtime. It’s also a vehicle for the Future of Life Institute, a longtermist secular church based on eugenic thinking. The Future of Life Institute shouldn’t be touched with a ten foot pole by anyone interested in actual human flourishing: FLI doesn’t care about you or anyone, they want to make sure that future digital beings somehow get spawned and their bit should be happy. They would be ridiculous if they didn’t weasel themselves into the discussion about “AI” and other technologies. Like they got themselves onto this declaration together with a bunch of fascists.

But maybe they case is just too good. Too important. I wrote about being able to form alliances lately, after all, didn’t I. (Just a quick note on that: There can never be an alliance with fascists. It doesn’t matter what they ask for. What they fight for. All you do with fascists is anything to stop them by all means necessary.)

So what are the important statements here? They are not too many so let’s have a quick look, shall we?

1. Keeping Humans in Charge

Human Control Is Non-Negotiable: Humanity must remain in control. Humans should choose how and whether to delegate decisions to AI systems.

Meaningful Human Control: Humans should have authority and capacity to understand, guide, proscribe, and override AI systems.

No Superintelligence Race: Development of superintelligence should be prohibited until there is broad scientific consensus that it can be done safely and controllably, and there is strong public buy-in.

Off-Switch: Powerful AI systems must have mechanisms that allow human operators to promptly shut them down.

No Reckless Architectures: AI systems must not be designed so that they can self-replicate, autonomously self-improve, resist shutdown, or control weapons of mass destruction.

Independent Oversight: Highly autonomous AI systems where controllability is not obvious require pre-development review and independent oversight: genuine authority to understand, prohibit, and override, not industry self-regulation.

Capability Honesty: AI companies must provide clear, accurate and honest representations of their systems’ capabilities and limitations.

Ahh the good old “human in the loop” shebang. Or as we who have lived in this world call it: The “take the fall for the decisions an automated machine made” trick.

There’s not much to this: “Humans” must be in control. What this omits is the question of which humans. Say today a few people (basically all of them very rich men) who are considered human are in control. Is that what they mean? Because sure as shit I am not. Maybe you are, I don’t know you. The claim that “humans” need control pretends that we are all one homogeneous mass but there are differences in power and access. Every monstrosity humanity did was under human control. Human control feels great because everyone reading it thinks it means them. It does not.

Then there’s the Sci-Fi angle. Nobody is allowed to build a machine god and it needs an off-switch so we can kill it before [INSERT RANDOM SCI FI MOVIE REFERENCE]. Sure whatever. We could write the same passage about rabit Unicorns because we have basically the same ability to bring those to life than we have with “Superintelligence”. The “self-replicating” thing goes into the same direction. This is just science fiction references to make everyone feel afraid. But that’s not real. It’s not addressing any actual harms that “AI” systems do – which there are many of – and shifts the whole discourse to talking about nothing really. Sure I also watched The Matrix, it was a cool movie. But we shouldn’t base our politics on it (except for understanding hat trans rights are human rights of course!).

I am a bit more charitable with the last two aspects: Sure oversight is good. All companies need way more oversight. But not by setting up a comfy oversight board for a few handpicked researchers, investors and activists who get flown to nice meetings debating whatever. Actual oversight needs teeth, needs the willingness to use them. And demanding that companies must be honest would be neat. Good luck with an “AI” sector where basically every CEO is a compulsive liar. But sure.

2. Avoiding Concentration of Power

No AI Monopolies: AI monopolies that concentrate power, stifle innovation, and imperil entrepreneurship must be avoided.

Shared Prosperity: The benefits and economic prosperity created by AI should be shared broadly.

No Corporate Welfare: AI corporations should not be exempted from regulatory oversight or receive government bailouts.

Genuine Value Creation: AI development should prioritize solving real problems and creating authentic value.

Democratic Authority Over Major Transitions: Decisions about AI’s role in transforming work, society, and civic life require democratic support, not unilateral corporate or government decree.

Avoid Societal Lock-In: AI development must not severely limit humanity’s future options or irreversibly limit our agency over our future.

This one is fun. Because if we took it seriously this would be the demand for democratic socialism or even democratic communism. Which I am totally on board with. But that’s probably not what these folks are aiming for.

TBH the fact that all these paragraphs add “AI” is cute because if you strip it out of the text this is a list of demands to reign in the tech sector and corporations in general. But that’s not on the agenda.

“No AI monopolies”. So other monopolies are okay? “Genuine Value Creation” and “solving real problems”. Yeah sure. But that also applies to fucking Microsoft or whoever invented vapes.

This whole part is pointing out things that are wrong with capitalism. Welcome comrades (no, not you Steve Bannon and your fascist buddies).

But it’s very explicitly not saying that. Because this is “AI”. “AI” is special. All the things labeled as problematic here happen every day. It has absolutely nothing to do with “AI”. This is just to get some buy in by connecting the actual experience of people having to live in late stage capitalism somehow to “AI”. But the thing breaking us is capitalism.

Another question: Who gets to decide what “genuine value” is? The dude who invented vapes can point at how he’s making all that money and how it creates economic activity. Is the advertising industry “creating authentic value”? What does that even mean? Are they arguing for full democratic control of the economy? Again: Big fan, let’s go, but in their reading is that not a contradiction to not “stifle innovation, and imperil entrepreneurship”?

You gotta pick one: Democratic control or unchained innovation and markets. Those things have more tension than me reading that smart and famous people sign a declaration with Steve fucking Bannon.

- Protecting the Human Experience

Defense of Family and Community Bonds: AI should not supplant the foundational relationships that give life meaning—family, friendship, faith communities, and local connections.

Child Protection: Companies must not be allowed to exploit children or undermine their wellbeing with AI interactions creating emotional attachment or leverage.

Right to Grow: AI companies should not be allowed to stunt children’s physical, mental or social growth or deprive them of essential experiences for healthy development during critical periods.

Pre-Deployment Safety Testing: Like drugs, chatbots must undergo pre-deployment testing for increased suicidal ideation, exacerbation of mental health disorders, escalation of acute crisis situations, and other known harms.

Bot-or-Not Labeling: AI-generated content that could reasonably be mistaken for human-generated must be clearly labeled as such.

No Deceptive Identity: AI should clearly and correctly identify itself as artificial, nonhuman, and not a professional, and it should not claim experiences it lacks.

No Behavioral Addiction: AIs should not cause addiction or compulsive use through manipulation, sycophantic validation, or attachment formation.

I could almost repeat what I wrote about the last segment: Yeah sure, but this has very little to do with “AI”. “AI” is built to create an addiction/dependency but most other digital systems at least try to do that, too. Sure, with “AI” it’s not longer Meta who is your dealer but OpenAI but in the end both companies see you just as resource to exploit. Nothing “AI” here.

Yes, companies should not build systems exploiting children. Who’s with me burning Roblox to the ground or every free to play game in existence?

But there is something where I can calm the signatories (who all thought that putting their name next to Steve Bannon was a good idea): The idea that “AI” systems need to be labeled is already the law in the EU. It’s interesting though that their demands are way less strict that existing laws: A bot only needs to label its output if it could be mistaken as human. So a bot making hiring decisions in some backend doesn’t need to be disclosed? That’s super weak.

And just a small nitpick here: “it should not claim experience it lacks”: No “AI” has any experience. They are buckets of floating point numbers with delusions of grandeur. Living beings existing in the world have experiences. Numbers do not.

4. Human Agency and Liberty

No AI Personhood: AI systems must not be granted legal personhood, and AI systems should not be designed such that they deserve personhood.

Trustworthiness: AI must be transparent, accountable, reliable, and free from perverse private or authoritarian interests.

Liberty: AI must not curtail individual liberty, freedom of speech, religious practice, or association.

Data Rights and Privacy: People should have power over their personal data, with rights to access, correct, and delete it from active systems, AI training sets, and derived inferences.

Psychological Privacy: AI should not be allowed to exploit data about the mental or emotional states of users.

Avoiding Enfeeblement: AI systems should be designed to empower, rather than enfeeble their users.

I also think that “AI” systems deserve no personhood. And since I believe that “the corporation” is for all intends and purposes one of the first forms of “AI” we should strip them of a lot of person rights that we have given them. Who’s with me? You cannot say that “AI” shouldn’t get personhood and then claim that corporations can. Personhood is for people. But that’s me being radical again.

Now I don’t know where “perverse” found its way into this document (probably one of the many, many, many religious groups involved here) but it surely reads a bit as if they are afraid that their “AI” might be too queer. But maybe I am too uncharitable here.

“AI” is supposed to be accountable. But who is accountable? A person is accountable for their actions. But we already said that “AI” is not a person. What does it mean for an “AI” to be “accountable” then?

We go on with “free speech”. Of course. But which understanding of that? In Germany denying the existence of the holocaust is illegal. Should your “AI” deny the existence of the holocaust? For freeze peach?

But it’s cute that under “data rights and privacy” they added a claim for GDPR.

“Psychological privacy”: Here’s the kicker. “AI” doesn’t exploit. The people who built and run it, do. But you do not talk about them.

“Avoiding enfeeblement”: Yeah big fan of that. But if you look at studies about cognitive offloading and its effects if you actually mean it, you can join me and my army of friends of Ned Ludd burning down a whole bunch of data centers. “AI”s are built to take your agency and capability.

5. Responsibility and Accountability for AI Companies

No Liability Shield: AI must not be able to act as a liability shield, preventing those deploying it from being legally responsible for their actions.

Developer Liability: Developers and deployers bear legal liability for defects, misrepresentation of capabilities, and inadequate safety controls, with statutes of limitation that account for harms emerging over time.

Personal Liability: There should be criminal penalties for executives responsible for prohibited child-targeted systems or ones causing catastrophic harm.

Independent Safety Standards: AI development shall be governed by independent safety standards and rigorous oversight.

No Regulatory Capture: AI companies must not be allowed undue influence over rules that govern them.

Failure Transparency: If an AI system causes harm, it should be possible to ascertain why as well as who is responsible.

AI Loyalty: AI systems performing functions in professions with fiduciary duties, such as health, finance, law, or therapy, must fulfill all of those duties, including mandated reporting, duty of care, conflict of interest disclosure, and informed consent.

Now. Here’s a surprise: I agree with a lot of what is written here. I have actually written about “that asterisk” before. We accept a level of “AI” companies delivering absolute garbage and putting it on us to “check” it. We would not accept that dynamic anywhere else. If I go to the supermarket to buy milk and all cartons had a post-it stuck to them saying “might be full of rat poison, you better check”, that store would just be closed.

“AI” currently is in the status of a supermarket that doesn’t know (and doesn’t care enough to check) if it’s delivering rat poison or not. Awesome.

I agree that “AI” companies should be liable for their product. I also think that people deploying and integrating these products should be liable.

And I also agree that we mustn’t let “AI” companies write or influence legislation.

This is the least bad part of the document. (You know the document that fascists also support and signed and respectable people not having a problem with that.)

The document itself isn’t that interesting. A bunch of half-assed, a bit contradicting demands that read a bit as if a chatbot helped writing them. A whole bunch of problems being correctly identified and then quickly attributed to “AI” instead of capitalism. Sure, it’s hard to challenge one’s beliefs but still: Aggregating this should have lead to some insight and thinking. Unless … this was written with a chatbot, right?

More interesting is definitely who signed it. Who thought that it was good to integrate fascists and white nationalists whose whole aim is to destroy the rule-based order that the world used to be in.

We see many organizations trying to show their relevance by being on this – sorta empty – paper. But they are also legitimizing a lot of problematic stuff here – The Fascists and The Future of Life Institute being just the first things that caught my eye and I am scared to look into the religious organizations and all the “ethical AI” orgs because usually when you start poking around something filthy comes up.

The whole document and activity is based on the assumption that “AI” is special. Needs special rules. Special approaches. But that ain’t true.

We need to regulate tech. Need to regulate how it is being used against us, our wellbeing, our rights in this world. But it doesn’t matter if the abuse commited by corporations and governments is done through a stochastic model, some other form of automation or just people: “AI”s mustn’t stifle our development and freedoms? Yeah, neither should people.

The grown up approach to regulating tech does not lie in building special rules for special technologies. That’s a sucker’s game that tech loves. Because it can drown the discourse in jargon and get a large influence because “only tech bros understand that stuff”. Fuck that.

Regulate outcomes. The tech doesn’t matter. For the person hurt the tool that was used to hurt them isn’t that relevant. We need to make sure that we are reducing, ideally eliminating the hurt.

Coda: I can’t get over how the whole document basically argues for democratic socialism/communism and the abolishment of capitalism. Looking at the organizations who pushed it and probably wrote most of it it shows a lack of self-awareness and critical thinking that is kinda cute. Like a baby right before it learns object permanence.

When we moved into our apartment we hired a contractor to build bespoke cupboards for a few niches that we wanted to use optimally. He built perfectly fitting, nice cupboards that make those areas look nice and clean while allowing us to store all kinds of stuff. And he took great care doing it.

Even after the job had started he kept explaining us why certain decisions we thought were smart might have been not so smart and offered solutions – often without charging extra. He wanted to build something that lasts and that makes us happy – while being fairly paid of course.

This s a privileged position: Being able to afford hiring an expert, finding one in your vicinity is not available to everyone. And not everything needs to be bespoke. Sometimes a well-thought, well-built off the shelf item is absolutely fine and a bespoke solution wouldn’t add anything but cost.

But what this extreme illustrates is the level of care that goes into building something well: The care a person takes in doing a good job but also understanding one’s work for someone else as a level of care towards that person. If you ask me to do something for you, me doing it means that I also take care of you to a certain degree. We have even codified that to a certain degree for many products where someone selling you something needs to give you warranty or other guaranties about whatever they sold you – mostly in order to try to protect people against capitalism’s tendency to make everything worse.

Software is an interesting product category in that a lot of software these days is no longer optional: It’s not a video game you can use or not but it’s the infrastructure that allows you to get paid, get government services, sign your kid up for school etc. These days we are mostly forced to use software whether we like to or not – often even software we cannot have any control over. This also means that building software should be increasingly more focused on people’s wellbeing and security: If you force people into something you need to make sure they are taken care of.

Of course we know that that’s not how things are. The quality of software we all interact with each day is perceivably worse than it used to be (we use MS 365 at work and boy is that a for of torture done to us by one of the biggest and most powerful companies in the world). Windows (and to a degree MacOs) is getting so bad that people are actively looking into running Linux. 1.0 versions of software neither mean that they work nor that they are feature complete, they are just whatever MVP compiled at the previously defined release date. You can always patch things later right? Well patches have gotten so bad that many people actively avoid installing them fearing what they might break.

It would be deeply unfair to just chalk that up to “AI” making software worse. Software was doing bad before, standards of quality being largely nonexistent. But “AI” and the promise that you can just magically create software is pouring gasoline on the fire: We are generating code way beyond our ability to ever review and ensure the security of. The developer of OpenClaw, the very hyped “AI” agent thing kept on proudly shouting on X, the everything Nazi app, that he’s constantly releasing code he never checked into the wild and into people’s personal infrastructure and data.

It’s the most visible rejection of care in software: People proudly saying how much the software they work on is “vibe coded” or “written by Claude” underlining how there is no pride in or responsibility for the work one not only put out but actually forces on people. It’s like a chef loudly stating that they didn’t even taste the menu they now want you to pay 200 EUR for. Like a doctor saying that they just describe you whatever medicine the computer tells them to without even looking at your test results. It’s a statement making clear that you do not give a shit. That you do not care.

Not every good can be produced artisanally: Furniture or clothes take a long time and skill to make, and in order to make them well you need good and expensive materials. It doesn’t scale up to the actual current need (which is way below the need that companies try to trick you into) and it’s too expensive for most people (That is a decision we as societies made when we forced people into jobs whose pay isn’t adequate to have a decent life. We could choose differently.)

But at least for software that is different. Digital goods (aside from “AI” which works differently) are characterized by 0 marginal cost meaning: Your costs don’t really go up when “producing” another copy of a software you already wrote.

This is where I see FLOSS – free and open source software – having their niche. Because in that space we can build situations and contexts where an artisanal mode of production, a mode based on care for the product and the people using it is feasible. Where not some millionaire or billionaire needs to squeeze out another few extra percent of profit every year by degrading the quality more and more.

I think FLOSS should embrace the small-scale, artisanal mindset. To build a stack of sustainable, high quality components while the rest of the world is trying to see how low the race to the bottom in software quality can go.

Writing software for people is important. It can also be fun. Especially when you get the time and (head)space to move carefully and intentionally. In that situation, software is just one way to show care for one another and act upon that display of love and respect.

We all deserve more software made with actual love for people.

I installed Marathon's Server Crush last week and, having loved all of its fancy trailers and soundtrack reveals to date, really enjoyed my brief introduction to the game's universe via a moody intro sequence before whipping through a guided tutorial against AI opponents while Marathon's basics were explained to me.

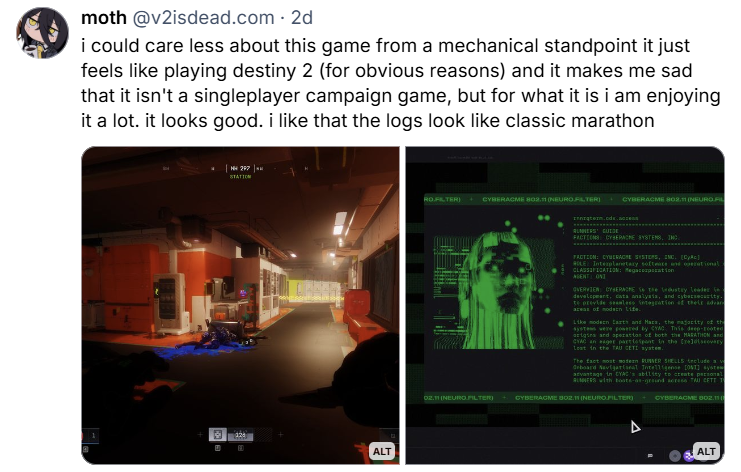

Trudging through some trailers and buildings while an alien storm erupted outside, I started clicking through its incredible menus, soaking up its stunningly vibrant art direction and just generally getting very into a world that's one of the most unique and interesting that AAA gaming has managed to serve up in years. And as soon as that tutorial was over, I quickly realised the same thing loads of you probably realised over the weekend as well: I wish this wasn't an extraction shooter.

We all know why it is. Developers Bungie have always excelled at multiplayer shooters, and a few years back their owners at Sony went so hard on live-service video games that it's now costing people (and entire studios) their jobs. And it's not like my "waahh I wish this was singleplayer" complaint is new; with its dense lore and memorable design, Marathon's predecessor Destiny could also have had a proper singleplayer element to it, but didn't and has turned out just fine.

Just because there's a logical explanation doesn't stop it being a huge bummer though. All that work that's gone into building such a detailed world, to construct all this backstory, the weather, the colours, the soundtrack, the vibes, all of it is just begging for some kind of singleplayer experience. Even if it's just a campaign, it’d be a way for me to get to know all these parts of the map at my own pace. I could poke my head into corners, rummage through drawers looking for audio logs, and get caught up in all kinds of cool, scripted shootouts.

For all Bungie's multiplayer pedigree--and I don't want to see Destiny's success or Halo's place in couch gaming folklore cut short here--I think the thing the studio has always done best has been singleplayer experiences. From Halo's epic original trilogy to the tension and surprise of ODST to the wonders of Reach and its iconic ending–it's getting tougher to remember as the years go by, but Halo and its sci-fi universe used to be so beloved and successful that it could have been, if not the next Star Wars, then at least something more interesting than Avatar. Halo 3's launch event was a moment in culture, touted as the "biggest entertainment launch in history"! Peter Jackson was going to make a Halo movie! Those games, and the singleplayer storylines underpinning them, were that good.

After years of non-Bungie Halo games failing to land a punch, and of Destiny catering only to a multiplayer crowd, I just want to feel that joy again. To play a Bungie game where a world is opened up in front of me like a box of toys, full of surprises and challenges and memorable moments, and which I can shoot my way through on my terms. Instead, Marathon is an extraction shooter. And it's fine? I played it for a bit and it's an extraction shooter alright. A type of game I simply have zero interest in, and even if I did, don't have the time for.

Like I said, I get why from a business sense this decision has been made, to the extent that there isn't even a singleplayer campaign. I just think that business sense is a bummer.

This week’s question comes to us from Anthea Tawia:

I came to San Francisco to visit the company I work for—sadly I was let go the first day I visited the office. I’m early in my career, worked there about 5ish months and really felt this was my big break. It’s disheartening to find yourself searching again after thinking you found what you’re looking for. How do you face a future that feels so uncertain?

First of all, I’m incredibly sorry this happened to you. It’s unforgivably brutal.

Secondly, I fear you’re about to be deeply disappointed in my answer because there is no easy answer to what you—and so many other people—are currently going through. I also refuse to engage in the type of toxic positivity that would tell you this is a good learning experience, or that it will all be alright. Because the former is a straight-up lie and the latter is questionable at best.

I’m sure other people have told you this, but it bears repeating not just for you but for anyone else reading this who might’ve recently lost their job: It’s not your fault, and there is nothing you could’ve done differently to change the outcome.

I’ll say it again: It’s not your fault, and there is nothing you could’ve done differently to change the outcome.

I’m assuming, just playing the odds here, that you work in tech. Probably in some design or design-adjacent capacity.

My own design and tech journey started under very different circumstances, at a very different time. I accidentally joined up almost at the very beginning, when things were more driven by curiosity than profit motives. And by “accidentally,” I mean that I had no clue this could be a career. None of us did. We had no idea what it was that we were making or how it would slot into the world, but either through naivete, hubris, prescience, or a combination of the three we felt this was something important, and overall positive. Words like “democratization,” “netizens,” and “new economy” were being thrown around with wild abandon. We were right about some things. It did change the world, but that was a massive monkey’s paw. We were wrong about other things. It was not overall positive. And we were ignorant about more things than we were right or wrong about combined. But by and large, there was the sense that the industry was attempting, if not always succeeding and certainly mired in the biases of white men, to make the world a better place.

It did feel, for at least a while, that we were doing a fair bit of solving problems, and making things that people enjoyed. Online banking and bill paying is nice. The iPod was cool. Cue cat? Very cool. Social media could’ve worked, maybe with different people in charge. 3D printers are cool. (I’ve made about 500 anti-ICE whistles this week!) Video cams were cool when we were pointing them at coffee pots and not our neighbors. Borrowing books from the library on an e-reader? Amazing.

Eventually, the industry did well enough to make a lot of people accidentally rich, which attracted people who were now expecting to get rich, and as with every new industry that eventually matures and goes into maintenance mode, a group of people who were pissed off they weren’t getting rich as quickly as the last group. And that’s when the problems that we were trying to solve switched from “what do people need” to “I’m not rich yet.” And eventually to “Ok, I’m richer than I ever need to be, but there is still some money, land, and water, over there that I want.”

But when I think back to myself at the start of my career, and the things that pulled me towards this industry, I don’t see myself making that same decision if I were making it now. This is not a place of honor.

As Pavel Samsonov so clearly and succinctly said recently on Bluesky: “Once, technology solved problems. People liked having problems solved, so they liked technology. Tech execs started to think of that sentiment as their due. So when they stopped solving problems, and people stopped liking them, they became outraged. ‘How dare you not love whatever we give you?’”

We do not love the surveillance. We do not love the slop. We do like paying rent and going to the doctor though. So we keep trying to do the work.

I think we need to open our eyes to the fact that the current industry many of us work in, not only doesn’t care about their workers, it actively resents them. In their eyes, we have gone from being the people who made things possible, to an unnecessary burden on the bottom line.

They hate that we charge money for our labor, and see that money as something we are stealing from their pockets. Which are very large, are already more full than they will ever be able to use in a lifetime.

They don’t want you to improve, they don’t want you to be more productive, they don’t even want you to be more pliable. They just want you gone. As I was writing this sentence I got an alert from a friend that Block, Jack Dorsey’s latest chewtoy, has laid off 4,000 people. Which made its stock rise 24%. When 4,000 people lose their livelihood, their ability to pay their rent, their ability to go to the doctor, their ability to look out for their children, and the system that we live under cheers that on… That system needs to be destroyed. Capitalism sees workers as a bug, not a feature. They are dying to eliminate us. Capitalism is not a system of honor.

If you are looking for a sliver of positivity in those last few paragraphs, it might be that five months into your career you still have time to walk back out and try another door. I realize that this is neither easy to do, nor uplifting, nor the answer you were looking for. But I feel like I am duty-bound to tell this industry is not a place of honor.

CEOs are handing out lucite to fascists. Companies are building massive surveillance networks to make kidnapping our neighbors easier. The world’s richest idiot has turned Twitter into a child pornography factory. VC firms are hiring partners whose only job qualification is that they’ve murdered Black people on the subway. And an industry that senses its own decline is now stuffing every product and service we’ve adopted with slop like slop is the only lifesaver left on the Titanic.

To make it even more depressing, as if that were necessary, when I look out at the evil bastards doing these things, celebrating the murder of my neighbors, I see many of the same faces who were talking about tech as a force for good when I first started. I see many of the same faces who were posting letters about the importance of diversity to their corporate sites in 2020. I see many of the same faces who promised to “do better,” after the brutal murder of George Floyd now calling for a bigger ICE presence on our streets. These are not people of honor.

Anthea, I am so far away from answering your question. So here I will attempt to do so, but I fear that you will not like my answer. However, I have too much respect for you to lie. Your last sentence was about facing a future that feels so uncertain. But I feel like a career in tech at this point is far from uncertain. In fact some things are more certain than uncertain. You would most likely be working for someone who doesn’t value you. You’d most likely be building something that is not improving the world. You’d most likely be forced to either spend your time babysitting the slop machine (and secretly fixing its mistakes) or actively working on the slop machine (and secretly pretending it was not full of mistakes). You’d be surrounded by over-eager 9-9-6 techbros who feel they’re temporarily embarrassed millionaires who don’t want the boot off workers’ necks as much as they envision their own foot inside the boot.

I know none of this feels good to hear. But I don’t think this industry deserves you. You deserve to work at a place that treats you with respect. A place that gives you the room to learn and grow, while cherishing the expertise you’re already walking through the door with. A place that pays you well and provides medical benefits for you and your family. A place with set hours, so you can flourish outside of work as well. A place where your opinion is not only welcome, but encouraged. A place where you feel safe. A place where you and the other workers can collectively bargain with management, because they understand that you are where the value comes from. I say these things not because you are special—although I’m sure you are!—but because all workers deserve these things.

Sadly, I fear those things are close to impossible to find in the tech industry at the moment. As you found out from direct experience. So I’d suggest asking yourself what you would be doing right now, if not for tech. Not because you don’t deserve to be here, but because it doesn’t deserve you.

If you decide to persevere in this industry, I’d walk into every interview with your head held high and remember that you are interviewing them, as much as they are interviewing you. You are deciding whether this is a company you want to sell your labor to. And I wouldn’t hesitate to walk out of any interview where you didn’t feel safe or valued. I’d walk the floor. I’d talk to other workers. (Outside work if possible.) I’d read up about the company. And I’d walk into that interview like I was doing a deposition. And of course, remember that none of this is a guarantee that they wouldn’t pull the same shit as your last company.

There is an uncertain future in front of you. And for that I am very sorry. Again, none of this was your fault, and there is nothing you could have done to keep it from happening. But in that uncertain future you may start finding things that you didn’t expect to find, maybe behind doors that you’d previously closed off. And maybe, hopefully, one of those will lead to a life full of joy and love. Keep in mind that a job will take up a huge percentage of your life, and this is not a practice life. It deserves to be amazing, not spent working for assholes. Life is wild, it doesn’t always go where you’re expecting it to. Shit sucks. Shit is unfair. Shit is brutal. Shit also makes strawberries. And whatever else we may do with our lives, we are all, at heart, strawberry farmers.

And for any tech leaders who are reading this and believe themselves the exception? Great. Show me. Instead of sending me the “not all tech leaders” email you’re already crafting in your head… do something to prove to us that it’s “not all tech leaders.” Take a stand. Call out your brethren. Refuse to work with Nazis. Stop licensing your software to Nazis. Start treating your workers with the respect they deserve. Every dollar in your very large pockets came from their labor. Share it.

And if you are running a company that respects its workers, and treats them honestly, and fairly? Hire Anthea. She seems awesome. You’d be lucky to have her.

📓 Some book news: If you’ve pre-ordered the new book, How to die (and other stories), thank you! I originally planned on getting all the pre-orders shipped out in February, but my printer has been sloooooooooow in getting books to me. Some orders have gone out. And there is a large shipment headed my way. I am sending books out in the order I received them. Fun fact: I asked a friend who works at a bookstore why things were slow and he told me every press in America is swamped right now, printing Heated Rivalry. Which honestly? I can’t get mad about that. I appreciate your patience. I love you.

🙋 Got a question? Ask it. I might meander myself into a useful answer.

💰 Join the $2 Lunch Club and help me pay my rent.

📣 The next Presenting w/Confidence workshop is scheduled for March 19 & 20. It’s a good workshop for folks interviewing.

🏳️⚧️ This week we are funneling all our help to the Trans Continental Pipeline. They’re busy getting trans people the fuck out of Kansas, and into Colorado. Because, yes, it’s come to this. Fuck these fascists.

They hate that we charge money for our labor, and see that money as something we are stealing from their pockets."